Why do tests make us stressed?

Imagine you are living 70,000 years ago. You walk out of your hut and straight into the face of a sabre tooth tiger. Your eyes meet. Stand off.

Your body has spotted the danger and started to act on it without even giving your brain chance to get involved. The vagus nerve has kicked in – an information superhighway between the brain and the body (Porges[1], 2005) running from your brain, via the facial nerves and heart all the way down to the gut. It raises the heart rate, shortens and quickens the breathing shallow. The pupils dilate to let in more light and vision. Your hip flexors engage so you can lift your legs quickly, and the shoulders round off to protect the chest, muscles tense: all of this is to get you ready to either run away or stay and fight.

Fast forward back to the present day, and you’re feeling the same sensations, but instead of a predator in your path, it’s a test on the screen in front of you. Or perhaps it’s just the thought of a test coming up. Herein lies the problem: given the desire to perform well in a test, we react to it in the same way as we do to a predator. But our bodies detect threat without us being conscious of the response (Porges, 2021[2]), giving the brain little say in the matter. In fact, most sophisticated brain functions such as logic, planning, language, creativity (all the things we need to do a test, no?), are deactivated when we are in this state.

So how can we stay calm for a test?

The good news is there is a hack! The vagus nerve is also responsible for calming us down and engaging social skills, logic, rest and digestion. We can use this body-brain highway to our advantage to manually override the stress response.

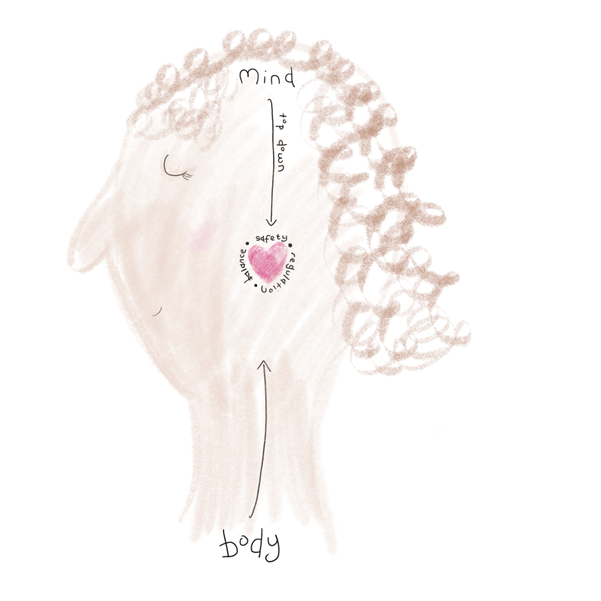

We have a stronger and bigger prefrontal cortex than our ancestors, the part of our brain responsible for these more sophisticated functions of the modern day human brain. Think of it like a watchtower. Often, we try to use this watchtower function to try and reason our way out of stress. However, only roughly 20% of information goes down from brain to the body (‘top-down’), whereas 80% travels upwards to the brain from the body (‘bottom-up’). So a more helpful approach is to go bottom up, using the body to give signals to the brain that we are actually safe, and bring the brain back online so it is ready to reason again[3].

Image: Top down/Bottom Up – Amy Malloy

Step 1 Breathe out slowly

Our exhale (breath out) switches on the calming branch of the vagus nerve, the parasympathetic nervous system, responsible for helping us rest and digest. By slowing our exhale down, we manually override the message being sent from the body to the brain, replacing it with one of safety instead of threat. The brain then stops releasing stress hormones and the rest of the body starts to calm too.

Step 2 Place one palm over your heart and one on your stomach

Consciously sensing our body wakes up our brain-body connection, grounding us back to the present moment and out of anxious thoughts.

Step 3 Watch the breath

Focus your attention on your breath. Watch your breath flow in to your nose, and out again, and how it moves in the chest and belly beneath your fingers. If your mind wanders, that’s normal – gently bring your attention back as many times as you need to. This continues to calm the body, but also brings our watchtower brain back online so we are conscious of what our body is doing again. This in turn wakes up our focus, helping us concentrate on the test questions.

This is mindfulness meditation. It really is that simple. Try it often.

An ancient spiritual practice, mindfulness meditation is backed today by countless scientific studies[4] to show it not only brings calm, clarity in difficult moments, but practised regularly it positively changes the wiring of our brain so we can notice and regulate our stress response before it takes hold. Rather than being a fixed state, our brains change depending on how we use them[5]. Regular practice can train our brain to use our watchtower function in a useful way: we can notice the physical symptoms of stress and make conscious choices to regulate our nervous system. In time, it can actually teach our nervous system not to see so many things as threats. In short, it gives our logical brain a say in the stress response again.

In short, mindfulness can be a reactive tool on the day, but also has incredible cumulative effects on our nervous system and mood over time. Regular practice of slow, steady breathing helps tone the vagus nerve, so the nervous system is more tolerant of stressful situations overall – think of it like a fitness programme for the nervous system.

In the webinar on Thursday 15th September, we explored all of this and more in further detail, including practical examples of the ideas suggested to help, with a toolkit to take away to use with your students and in your own life. You can try guided meditation, as we did in the webinar, in this video.

Amy Malloy is an illustrator, educator and mindfulness practitioner with a special interest in using creativity, story and breath for mental health and connection. After over a decade’s experience in educational publishing and assessment, she now brings her love of illustration and wellbeing to education. You can learn more about her work at www.theworldofamy.com

[1] Porges SW. (2005). Orienting in a defensive world: Mammalian modifications of our evolutionary heritage: A Polyvagal Theory. Psychophysiology. 1995;32:301–318

[2] Porges, S.W. (2021). Polyvagal Theory: A biobehavioral journey to sociality. Comprehensive Psychoneuroendocrinology, 7, p.100069. doi:10.1016/j.cpnec.2021.100069.

[3] https://www.verywellmind.com/an-overview-of-coherent-breathing-4178943

[4] Davis, D.M. and Hayes, J.A. (2011). What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy, [online] 48(2), pp.198–208. doi:10.1037/a0022062.